Cognitive vs emotional empathy represents the distinction between intellectually understanding another person’s perspective versus viscerally feeling their emotions. While cognitive empathy involves “perspective-taking” and the logical comprehension of mental states, emotional empathy (or affective empathy) is the automatic, physiological reaction to someone else’s feelings, often driven by mirror neurons and emotional contagion.

The Neurobiology of Empathy: Mirror Neurons and Beyond

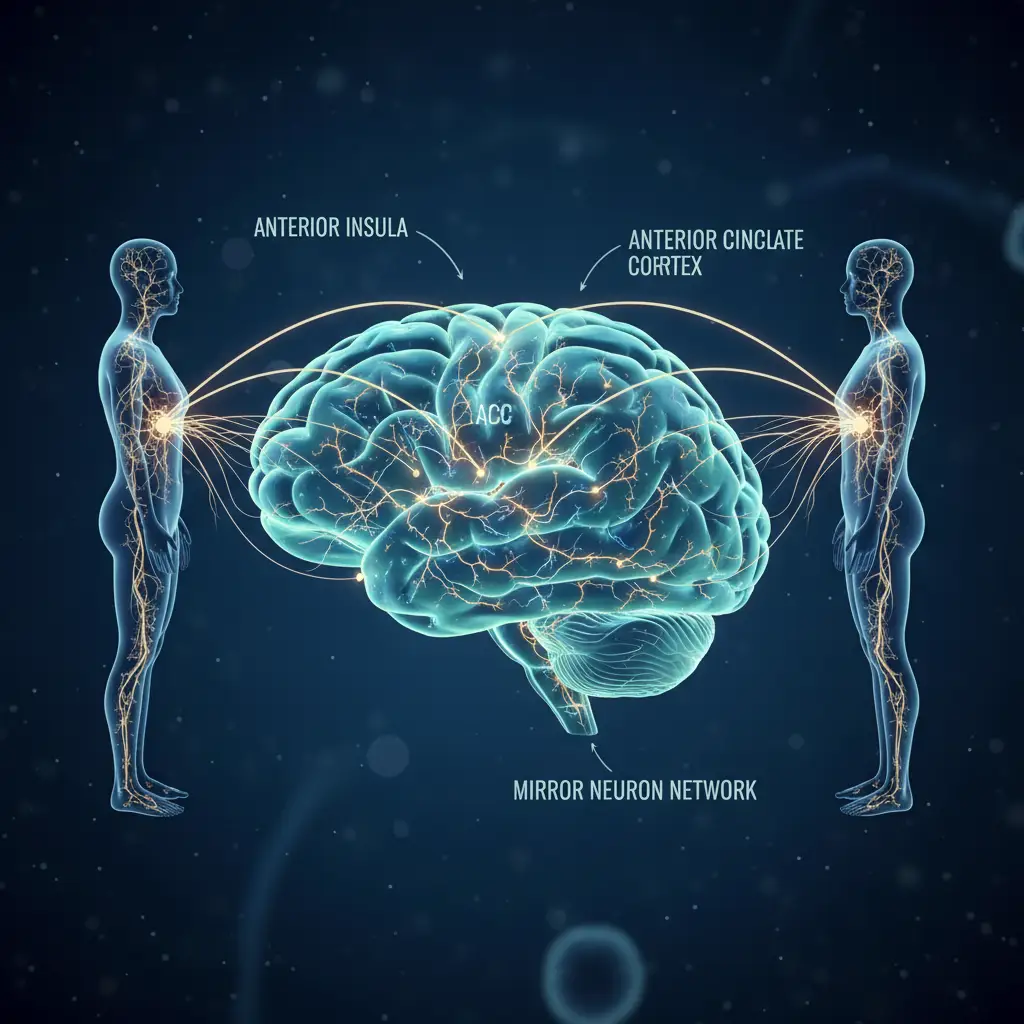

To truly grasp the nuances of cognitive vs emotional empathy, one must first look at the hardware of the human brain. Empathy is not merely a poetic concept of “walking in someone else’s shoes”; it is a complex biological process rooted in specific neural pathways. The discovery of mirror neurons revolutionized our understanding of how we connect with others.

Mirror neurons are a class of neurons that fire both when an individual acts and when the individual observes the same action performed by another. For example, if you see someone stub their toe, the neurons in your brain associated with pain perception light up, simulating the experience without the physical injury. This neural mimicry is the biological foundation of emotional empathy.

However, the science extends beyond simple mimicry. Research indicates that different types of empathy utilize distinct brain networks:

- The Emotional Network: Involves the anterior insula and the anterior cingulate cortex. This system allows us to resonate with the pain or joy of others rapidly and automatically.

- The Cognitive Network: Involves the prefrontal cortex and the temporal poles. This system is responsible for “Theory of Mind”—the ability to attribute mental states to oneself and others.

According to research published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), these systems can operate independently, which explains why a person might understand someone’s pain intellectually without feeling it, or vice versa. This biological separation is the crux of the distinction between cognitive and emotional empathy.

Understanding Cognitive Empathy: The Art of Perspective Taking

Cognitive empathy, often referred to as “perspective-taking,” is the ability to identify and understand another person’s emotions and mental state. It is a deliberate, top-down processing mechanism where the brain uses logic, memory, and social cues to deduce what someone else is thinking or feeling.

The Mechanics of Theory of Mind

At the heart of cognitive empathy is a psychological concept known as Theory of Mind. This is the developmental ability to recognize that others have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives that differ from one’s own. When you exercise cognitive empathy, you are essentially stepping out of your own psychological framework and stepping into another’s to analyze their situation objectively.

Applications in Leadership and Negotiation

Cognitive empathy is highly valued in professional settings. A negotiator, for instance, relies heavily on cognitive empathy to understand the opposing party’s motivations without getting emotionally swept away by the tension of the room. Similarly, a surgeon must understand a patient’s fear to communicate effectively but must suppress emotional empathy to perform the surgery with steady hands.

However, cognitive empathy has a neutral moral compass. Because it is an intellectual skill, it can be used for benevolence (helping a friend solve a problem) or manipulation (predicting a victim’s behavior to exploit them). This is why individuals with certain personality disorders, such as narcissism or psychopathy, may display high levels of cognitive empathy while lacking the emotional counterpart.

Exploring Emotional Empathy: The Power of Feeling With

Emotional empathy, also known as affective empathy, is the capacity to respond with an appropriate emotion to another’s mental states. It is the visceral sensation of “feeling with” someone. If cognitive empathy is knowing someone is sad, emotional empathy is feeling a lump in your throat when you see them cry.

Emotional Contagion

This form of empathy is often driven by emotional contagion, a primitive form of empathy where emotions spread from one person to another like a virus. Have you ever walked into a room where everyone was laughing, and you started smiling before you even knew the joke? That is emotional contagion at work. It serves an evolutionary purpose, allowing groups to synchronize their emotional states for social bonding and survival.

The Role of Somatosensory Resonance

Emotional empathy involves the somatosensory cortex, the part of the brain that processes physical sensations. When you witness suffering, your body may react with increased heart rate, sweating, or even phantom pain. This physical resonance makes emotional empathy a powerful motivator for altruism. It is difficult to ignore the suffering of others when you are physically sharing in their distress.

Cognitive vs Emotional Empathy: A Comparative Analysis

While both forms of empathy are essential for healthy human interaction, distinguishing between them is vital for understanding relationship dynamics and emotional intelligence. Below is a breakdown of the primary differences.

1. Origin of Processing

Cognitive Empathy is a “top-down” process. It starts in the higher reasoning centers of the brain (prefrontal cortex) and works its way down to understanding. It requires conscious effort and focus.

Emotional Empathy is a “bottom-up” process. It begins with sensory input (seeing a facial expression) that triggers the limbic system (the emotional brain) almost instantaneously.

2. Accuracy vs. Intensity

Cognitive empathy aims for accuracy. The goal is to build a correct model of the other person’s mind. Emotional empathy is characterized by intensity. It is not always accurate—you might feel stressed because your partner is stressed, even if you don’t know why—but the shared feeling is intense and undeniable.

3. Vulnerability to Burnout

Cognitive empathy generally consumes mental energy (like solving a math problem), but it is less likely to cause emotional exhaustion. Emotional empathy, however, requires a significant emotional toll. Constantly absorbing the feelings of others without regulation can lead to severe psychological distress.

The Double-Edged Sword: Compassion Fatigue and Burnout

One of the most critical aspects of the “cognitive vs emotional empathy” discussion is the risk associated with high levels of emotional empathy. This phenomenon is known as compassion fatigue or empathic distress.

When an individual relies too heavily on emotional empathy, the boundaries between self and other become blurred. In caregiving professions—such as nursing, social work, or therapy—this is a common occupational hazard. If a doctor deeply felt the pain of every patient they treated, they would quickly become incapacitated by grief and trauma.

Empathic Distress vs. Compassion

Neuroscientific studies suggest that empathic distress (feeling the other’s pain) activates pain networks in the brain. In contrast, compassion (feeling concern and a desire to help) activates reward and affiliation networks. The goal for high-functioning empathy is to move from empathic distress (a negative feeling) to compassion (a positive, proactive motivation).

Strategies to mitigate compassion fatigue include:

- Mindfulness Training: Learning to observe emotions without becoming attached to them.

- Cognitive Reframing: Using cognitive empathy to understand the situation logically rather than just feeling it viscerally.

- Boundaries: Establishing psychological limits to protect one’s own emotional well-being.

Integrating Head and Heart: Achieving Compassionate Empathy

The ideal state of emotional intelligence is not choosing between cognitive vs emotional empathy, but rather integrating them into a third state often called Compassionate Empathy or “Empathic Concern.”

Compassionate empathy strikes the perfect balance. It utilizes cognitive empathy to understand the predicament and the best course of action, while using emotional empathy to connect with the person and validate their experience. However, it regulates the emotional inflow to prevent overwhelm, channeling that energy into constructive help.

Steps to Balance Your Empathy

- Identify Your Default: Are you naturally a fixer (Cognitive) or a feeler (Emotional)? Acknowledge your baseline.

- Practice Active Listening: Use cognitive empathy to listen to the words and logic, but allow yourself to momentarily feel the emotion behind them.

- Pause and Regulate: If you feel flooded (too much emotional empathy), take a breath. Engage your prefrontal cortex to analyze the situation.

- Ask Questions: Validate your cognitive understanding. “It sounds like you feel frustrated because… is that right?” This bridges the gap between logic and feeling.

By mastering both the science of perspective-taking and the art of shared feeling, we can navigate the complexities of human relationships with greater depth, resilience, and authenticity.

People Also Ask

Can you have cognitive empathy without emotional empathy?

Yes, it is possible to possess cognitive empathy without emotional empathy. This dissociation is often observed in individuals with certain personality traits, such as narcissism or psychopathy. They can intellectually understand and predict another person’s emotions and behavior (perspective-taking) but do not experience the physiological or visceral reaction (feeling with) that typically accompanies those emotions.

Which type of empathy is better: cognitive or emotional?

Neither type is inherently “better”; they serve different purposes. Emotional empathy is crucial for deep personal connection, bonding, and immediate compassionate response. Cognitive empathy is essential for problem-solving, negotiation, and maintaining professional boundaries. The most emotionally intelligent individuals integrate both to practice “compassionate empathy.”

Is empathy genetic or learned?

Empathy is a mix of both genetic predisposition and learned behavior. While humans are born with the neural hardware for empathy (such as mirror neurons), the capacity is significantly shaped by early childhood attachment, socialization, and culture. Cognitive empathy, in particular, is a skill that can be developed and refined throughout adulthood.

Do narcissists have cognitive empathy?

Yes, many narcissists possess average or even high levels of cognitive empathy. They are often skilled at reading people and understanding what others are thinking or feeling. However, they typically lack emotional empathy, meaning they do not care about the pain those feelings cause, which allows them to use their understanding for manipulation rather than connection.

How can I improve my emotional empathy?

To improve emotional empathy, focus on active listening and being present. Practice vulnerability by allowing yourself to feel emotions rather than suppressing them. engaging in fiction reading or watching emotional films can also stimulate the brain’s empathetic pathways. Mindfulness meditation helps in becoming more attuned to your own bodily sensations, which is a precursor to feeling others’ emotions.

What is the difference between empathy and sympathy?

Empathy involves experiencing the feelings of another person (feeling with them), whereas sympathy involves feeling pity or sorrow for another person without necessarily understanding or sharing their emotional state. Empathy creates connection; sympathy can sometimes create a sense of detachment or hierarchy.