Parenting advice NZ encompasses the holistic guidance required to raise children within Aotearoa’s unique legal and cultural landscape, specifically focusing on the Care of Children Act 2004, the dynamics of blended families, and the integration of Te Ao Māori values. To succeed, caregivers must balance legal guardianship responsibilities with emotional support to ensure the welfare and best interests of their tamariki.

Raising children in New Zealand is a journey that weaves together traditional values, modern realities, and specific legal frameworks. Whether you are part of a nuclear unit, a single-parent household, or a complex blended whānau, the goal remains the same: providing a safe, nurturing environment where tamariki (children) can thrive. This guide provides comprehensive parenting advice tailored to the New Zealand context, addressing the emotional intricacies of family dynamics and the statutory realities of family law.

Navigating Modern Family Structures in Aotearoa

The concept of the ‘traditional’ nuclear family in New Zealand has evolved significantly over the last few decades. Today, whānau structures are as diverse as the landscape itself. From multigenerational households where grandparents play a pivotal role in daily care, to co-parenting arrangements across two households, the definition of family has expanded.

Understanding this evolution is critical for effective parenting. The ‘village’ mentality is making a resurgence, driven by economic necessity and a cultural recognition that raising children requires community support. In many Kiwi households, non-biological caregivers—partners, aunties, and close friends—often shoulder significant parenting responsibilities. However, navigating these structures requires clear communication and boundary setting.

Modern parenting advice in NZ emphasizes flexibility. Rigid adherence to old models can lead to conflict, particularly when managing expectations around discipline and financial contribution. Successful modern families prioritize the child’s stability over the adults’ relationship labels. This child-centric approach is not just a psychological recommendation; it is the cornerstone of New Zealand family law.

Legal Rights: Guardianship and Day-to-Day Care

One of the most confusing aspects for parents seeking advice is the legal terminology used in New Zealand. Unlike the American terms “custody” and “visitation,” New Zealand law, primarily under the Care of Children Act 2004, uses “guardianship,” “day-to-day care,” and “contact.” Understanding these distinctions is vital for avoiding conflict and ensuring you are acting within your rights.

Guardianship vs. Day-to-Day Care

Guardianship refers to the legal responsibility and right to make important decisions about a child’s upbringing. This includes decisions regarding religion, medical treatment, education, and where the child lives. In New Zealand, a child’s biological mother and father (if listed on the birth certificate or married/living with the mother at the time of birth) are usually joint guardians. Guardianship does not end when parents separate.

Day-to-day care refers to who the child lives with on a daily basis. A parent can have day-to-day care but share guardianship with the other parent. This means that while you might decide what the child eats for breakfast (day-to-day care), you cannot unilaterally decide to move the child to Australia or change their school without the other guardian’s consent.

Dispute Resolution

When guardians cannot agree, the Family Court encourages, and often mandates, mediation through services like Family Dispute Resolution (FDR) before a judge intervenes. The court’s paramount consideration is always the welfare and best interests of the child. For detailed information on these legal structures, the New Zealand Ministry of Justice provides extensive resources outlining the steps for parenting orders and agreements.

Cultural Approaches to Raising Tamariki

Parenting advice in NZ is incomplete without acknowledging the profound influence of Te Ao Māori (the Māori world view). Even for non-Māori families, these principles offer a robust framework for raising resilient, connected children.

Whanaungatanga (Kinship and Connection)

Whanaungatanga goes beyond immediate blood ties; it is about building relationships and a sense of belonging. For tamariki, knowing who they are and where they come from is essential for mental well-being. In a parenting context, this means actively fostering connections with extended family and community. It discourages isolation and encourages shared responsibility for the child’s growth.

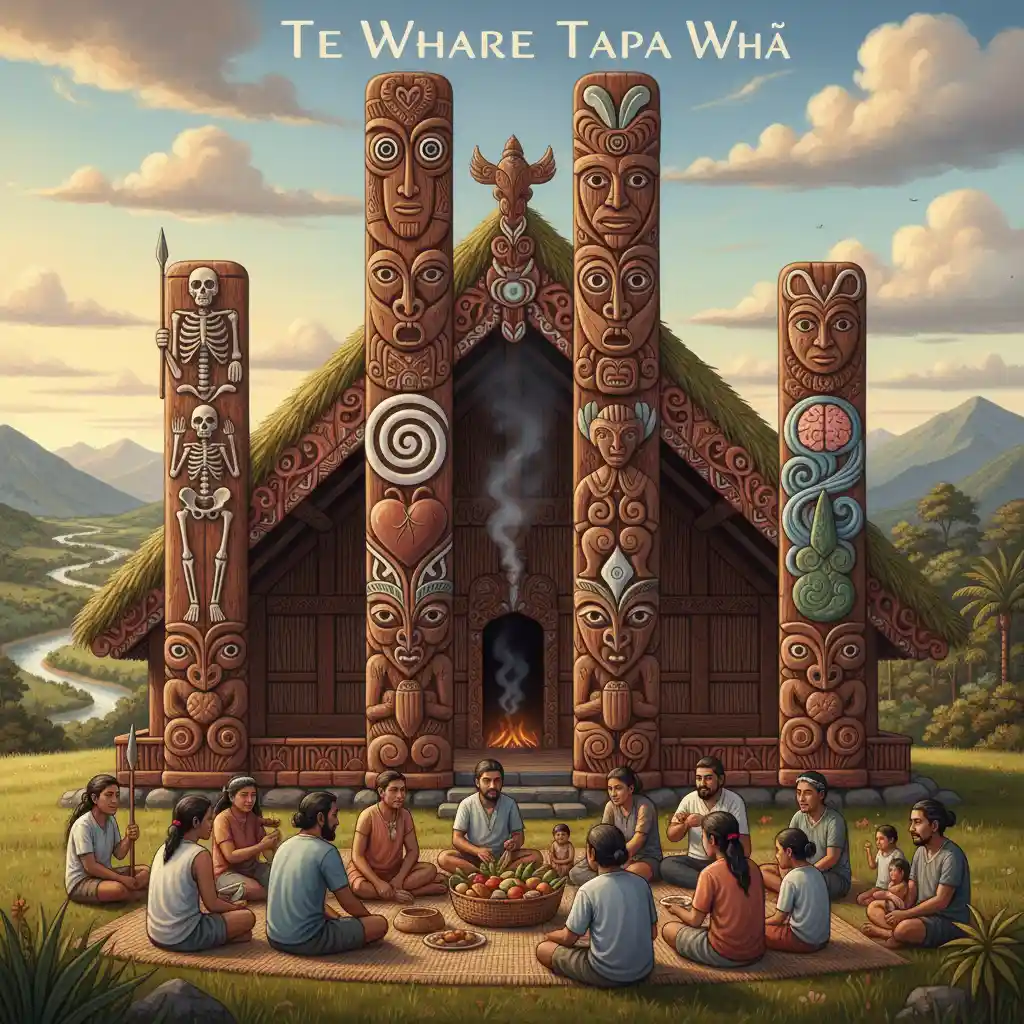

Te Whare Tapa Whā

Developed by Sir Mason Durie, this model of health is an excellent parenting tool. It views a child’s well-being as four walls of a house:

- Taha Tinana (Physical Health): Nutrition, sleep, and physical safety.

- Taha Wairua (Spiritual Health): Identity, values, and a sense of purpose.

- Taha Whānau (Family Health): Social support and belonging.

- Taha Hinengaro (Mental Health): Emotional regulation and learning.

When a child is acting out or struggling, this model prompts parents to look at which “wall” might be weak. Is the child physically tired? Do they feel disconnected from the family? This holistic approach moves away from simple punitive discipline toward understanding the root cause of behavior.

Mastering Whānau Dynamics in Blended Families

Blended families are common in New Zealand, but they come with a unique set of challenges often referred to as the “stepparent trap.” Blending two families involves more than just moving in together; it involves merging different parenting styles, household rules, and loyalties.

The Role of the Step-Parent

The most consistent parenting advice for new step-parents is to prioritize connection before correction. Children often resent discipline from a new partner, viewing it as an intrusion. It is generally recommended that the biological parent retains the primary disciplinarian role in the early stages of a blended family, while the step-parent focuses on building a supportive, non-authoritative relationship.

Managing Loyalty Binds

Children in blended families often experience intense loyalty binds. They may feel that liking their step-parent is a betrayal of their other biological parent. It is crucial for all adults involved to validate the child’s feelings. Avoid speaking negatively about the other household. In New Zealand, the Family Court views parental alienation—where one parent turns the child against the other—very seriously, as it is considered psychologically damaging to the child.

Effective Co-Parenting After Separation

Successful co-parenting requires treating the relationship with your ex-partner as a business arrangement where the “business” is the well-being of your child. Emotions must be managed to ensure communication remains constructive.

Communication Protocols

Use technology to your advantage. Apps that manage schedules and shared expenses can reduce the need for direct emotional engagement. Keep messages brief, factual, and child-focused. If verbal communication frequently devolves into arguments, switch to written communication entirely.

Parallel Parenting

For high-conflict situations where collaborative co-parenting is impossible, “parallel parenting” is a viable strategy. In this model, parents disengage from each other while maintaining a relationship with the child. Each household operates independently with its own rules. While consistency between homes is ideal, children are adaptable and can learn that “Mum’s house has these rules, and Dad’s house has those rules,” provided they are safe and loved in both environments.

Accessing Support Networks in New Zealand

No parent should have to navigate these challenges alone. New Zealand offers a robust network of support services designed to assist with everything from newborn care to legal advice for teenagers.

Plunket is a cornerstone of NZ parenting, providing free health and development checks for children under five. For older children and specific behavioral issues, organizations like Barnardos and Parent Help offer counseling and helplines.

For legal and relationship support, Community Law Centres provide free legal advice, which is invaluable for understanding guardianship disputes. Additionally, Whānau Āwhina Plunket offers resources that bridge the gap between clinical health advice and community support.

Parenting in New Zealand is a journey of balancing rights with responsibilities, and tradition with modernity. By understanding the legal framework of the Care of Children Act, embracing the holistic values of Te Whare Tapa Whā, and navigating blended family dynamics with patience, you can provide the stability your tamariki need to flourish.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between guardianship and custody in NZ?

In New Zealand law, “custody” is now called “day-to-day care,” which refers to who the child lives with. “Guardianship” refers to the legal right to make major decisions about the child’s life, such as education, religion, and medical care. Most parents remain joint guardians even if one has primary day-to-day care.

At what age can a child decide who to live with in NZ?

There is no specific age where a child can choose. However, under the Care of Children Act, the views of the child must be taken into account, and their opinion carries more weight as they get older and more mature. Generally, by the teenage years (12-14+), their preferences are significant factors in court decisions.

Do step-parents have legal rights in New Zealand?

Step-parents do not automatically have guardianship or day-to-day care rights. However, they can apply to the court to be appointed as an additional guardian or to have day-to-day care rights, especially if they have played a significant role in the child’s life.

How is child support calculated in NZ?

Child support is calculated by Inland Revenue (IRD) using a formula that considers both parents’ taxable incomes, the amount of time the child spends in each parent’s care, and the cost of raising children in New Zealand.

What is a Parenting Order?

A Parenting Order is a court order enforced by the Family Court that sets out who has day-to-day care of the children and when the other parent has contact. It is legally binding, and breaching it can lead to legal consequences.

Where can I get free parenting advice in NZ?

Free parenting advice is available through Plunket (for under 5s), Parent Help (helpline 0800 568 856), and Barnardos. For legal parenting advice, Community Law Centres offer free initial consultations.